“Horoscopes have become a ‘code for feelings’ in our everyday lives, which I think is really interesting. I think about my steel glyphs that way as well,” says artist and educator Maia Ruth Lee. “I mentioned talismans, and that is what I mean by it: using these glyphs to ward off certain negative aspects of your life.” Welded from discarded fragments of metal gates and fences, Lee’s glyphs evoke forms akin to ancient typography. Along with her extensive lexicon of steel glyphs, Lee self-publishes glyph charts, which look like handouts from New York’s Chinatown or the streets of Kathmandu. Most recently Lee showed her glyphs at the Whitney Biennial 2019 in the piece LABYRINTH.

Born in, Busan South Korea, Lee traverses many worlds: art, teaching, and self-publishing. Lee’s first solo exhibition in New York was at Eli Ping Frances Perkins in 2016, followed by her solo exhibition at Jack Hanley Gallery two years later. She has participated in numerous group exhibitions including at CANADA gallery (New York), Salon 94 (New York), Roberts & Tilton Gallery (Los Angeles), and Parisian Laundry Gallery (Montreal). Lee participated in the Whitney Biennial 2019 and was the recipient of the Rema Hort Mann Grant in 2017. She is the director of the nonprofit after school art program Wide Rainbow.

In a recent conversation, Lee discussed how visceral and intuitive it is to make symbols and signs, how a symbol can weld the everyday, and how the mystical can be welded with ease.

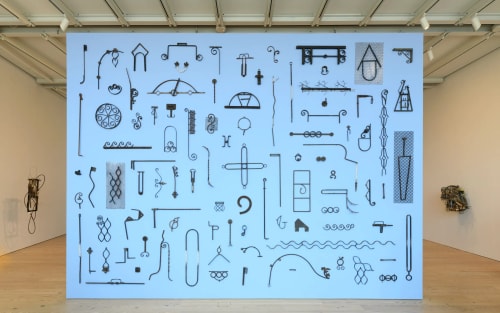

I first saw your work at the NY Art Book Fair in 2015. It was eye-opening to see your glyphs all on a wall at once in a publishing/design context. I wanted to begin by asking: what do publishing and design mean to you.

MAIA RUTH LEE (MRL)

Wow, that was such a long time ago, and it makes me happy to know someone saw those works. That was the first time I had ever made the steel glyphs. My husband and artist Peter Sutherland and I had a table at NYABF for years, and that year I was inspired to create something that was outside of the box. Publishing (more than design) has been part of my life since after I graduated from college in Seoul. I was in an artist collective, and we decided to start a bilingual art and culture magazine so we could publish our friends from Korea and abroad. I knew nothing about design, so I learned how to use Photoshop, Illustrator, and InDesign on YouTube. Everything was DIY then, and I loved it. It so happened to become one of the first self-published zines in the Korean art community.

SB

How did your early encounters with publishing and DIY culture inform your artistic practice?

MRL

DIY culture is exciting because there is no right or wrong. I think that opens up a lot of possibilities for one as an artist. Exploration becomes a real process and an open platform where many can share their experiences with each other without judgement.

SB

2 : a symbolic figure or a character (as in the Mayan system of writing) usually incised or carved in relief.

3 : a symbol (such as a curved arrow on a road sign) that conveys information nonverbally.

MRL

My steel glyphs are a cross between pictographs and talismans.

SB

Can you tell us more about the materiality of the glyphs and how you construct them?

MRL

The steel glyphs are constructed with scrap metal—specifically, low-grade steel—that are leftovers from fences, windows, or structures that are usually built for security or delineating boundaries. My process is quite simple; I drive around from neighborhood to neighborhood in New York to salvage metal from hole-in-the-wall metal shops. Sometimes I will hit a goldmine and there will be boxes of scraps, or sometimes they will have none. I bring them directly to a welding shop next to my studio and compose them on a huge metal table, and the welder will zap them into place. There is no sketch or preparation, so the process is fluid, intuitive, and fun. I bring them back to my studio and that is when the work begins. I categorize them into groups or “bodies,” and I assign each steel glyph a meaning. Of the approximately 250 glyphs I have made thus far, I’ve not thrown out any.

SB

You have mentioned how “symbols and signs in general are very intuitive anyway.” What else did making these glyphs tell you about symbols, signs, and language and its uses?

MRL

Our eyes have looked at symbols and signs in a specific way since prehistoric ages. I think that information has traveled down to the present in ways we cannot describe or analyze. When creating the steel glyphs I felt this to be true, when composing certain scraps together to create a larger glyph I could see that there were certain curvatures and shapes that would recur, and signifiers I would use to make the pieces look like ancient typography.

SB

I wanted to particularly focus on the glyph charts you make with each series of glyphs. They are fascinating artifacts from a design standpoint. Could we see them all side by side? Where did you get the idea of arranging the glyphs in this format? I feel they are invoking a specific vernacular and are in a way a key to the world of your language. Could you unpack the formal decisions you make while writing and laying them out?

MRL

Here they are:

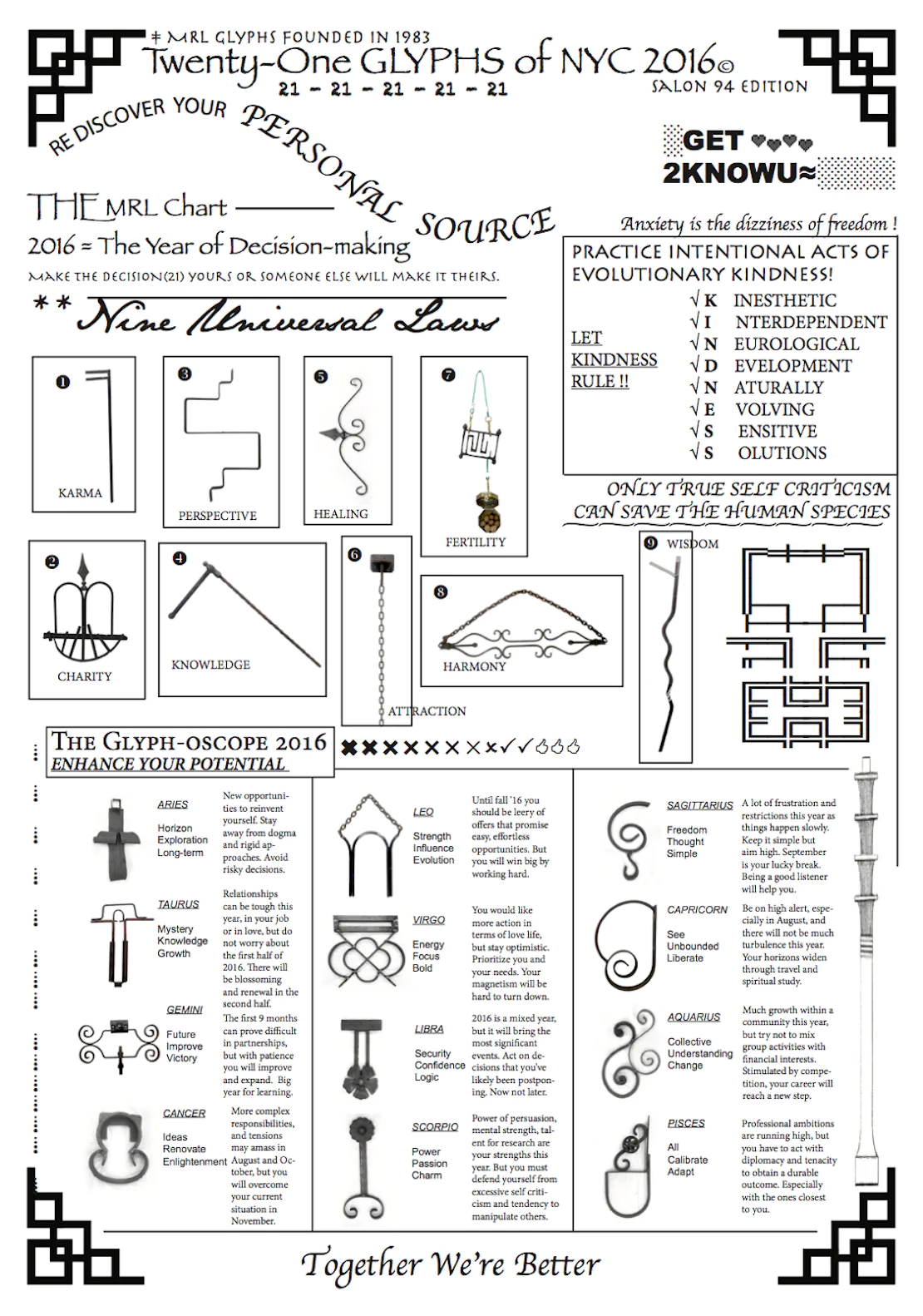

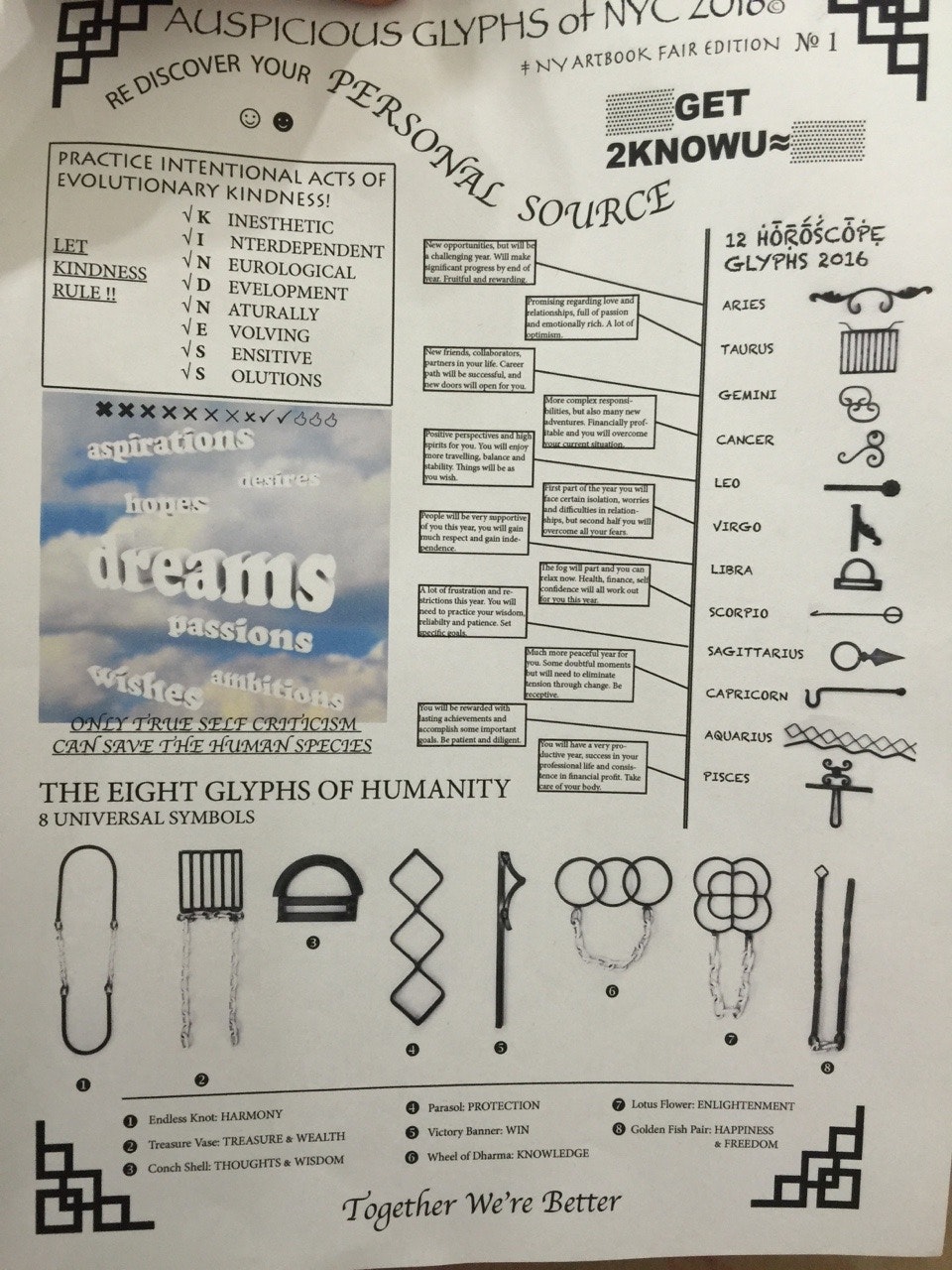

Glyphchart I, 2016

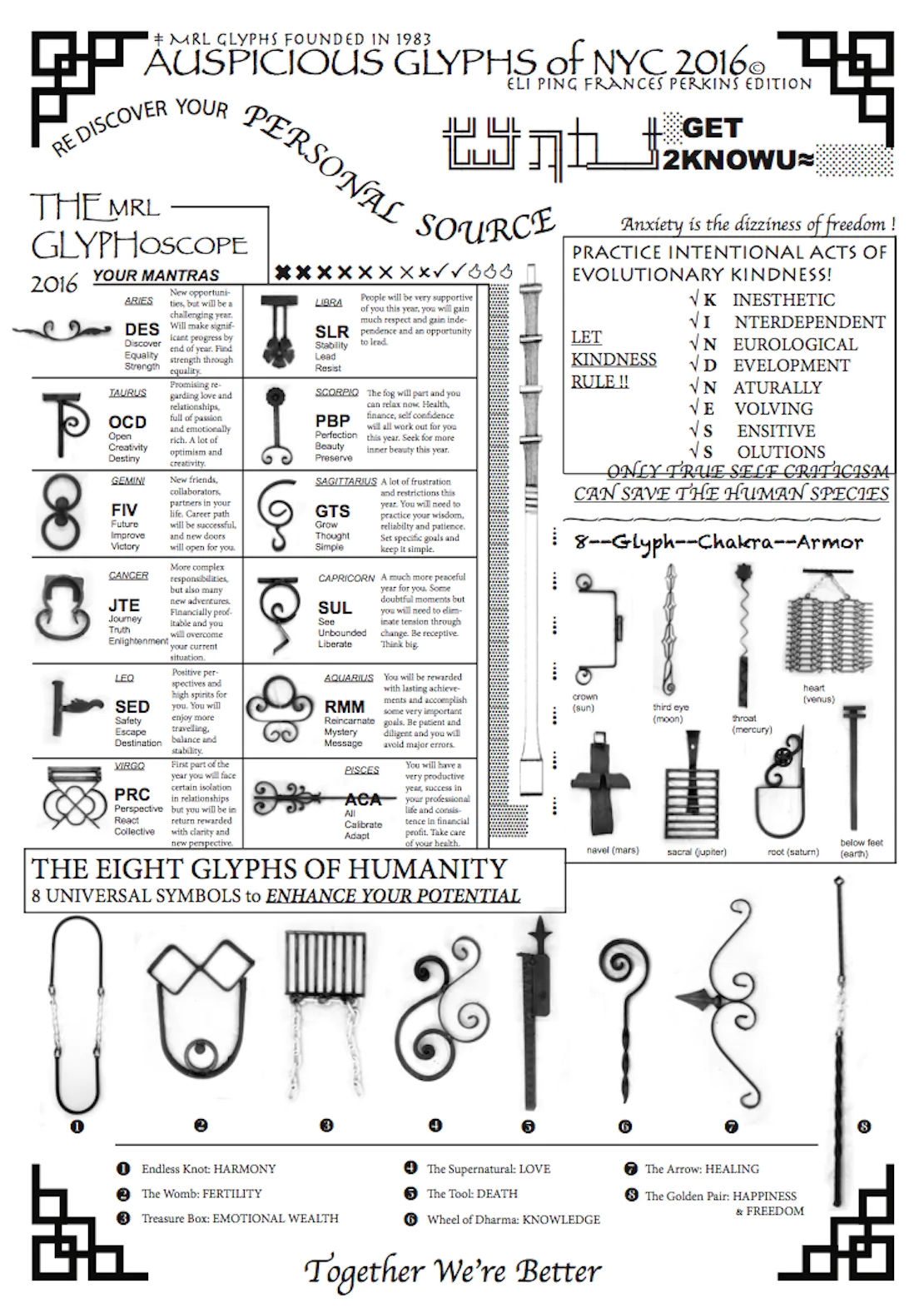

Glyphchart II, from 2016

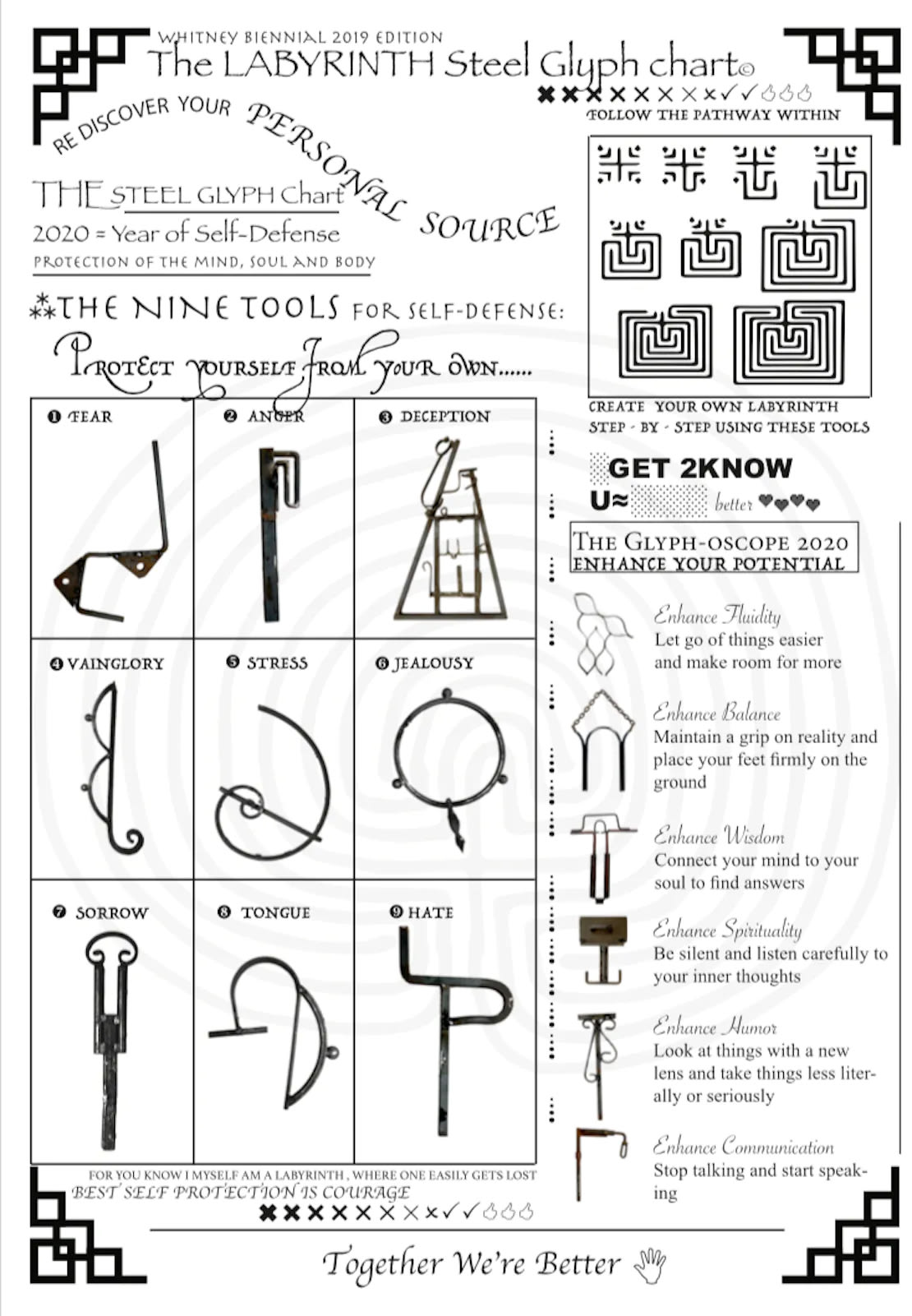

Glyphchart, 2019

First ever Glyphchart

I don’t have a design background so it was easy to create the chart without much thought on design taboos. I wanted these “keys” to look like a pamphlet that could be handed out on the streets in Chinatown or Kathmandu (where I grew up). Which means, I wanted to create something that was made for the people, designed by the people, and easily carries information and isn’t interfered with by design aesthetics.

SB

Do you sometimes feel language or aesthetics can become a burden? Or a violent, restrictive force?

MRL

Sometimes they can be a burden. I think it can be restrictive in the form of information overload. I fluently speak two languages, and I think it sometimes restricts the way I express because I’m always looking for the right way to communicate, and the words can get lost in translation.

SB

Your parents are linguists. What thoughts do they have on your glyphs? Your son, Nima?

MRL

My parents think it’s quite amusing, but they are quite serious people and at the end of the day don’t really get what I’m every making or doing. I don’t take it personally, it’s just the way they are. I’m not sure what Nima thinks. I hope he likes my art when he’s older!

SB

Can you tell me about the relationship your glyphs have to affect? In a way they are guardians of emotions, no? I would like to understand your take how a syntax can codify feelings.

MRL

Codifying feelings is a good way to put it. I love the obsession we have with astrology, for example. It feels like pseudo-spirituality, but at the same time it’s an ancient method of reading the stars. Horoscopes have become a “code for feelings” in our everyday lives, which I think is really interesting. I think about my steel glyphs that way as well. I mentioned talismand, and that is what I mean by it. Using these glyphs to ward off certain negative aspects of your life for example. It’s amusing.

Heart (Venus) Glyph

Heart (Venus) Glyph

Taurus, OCD (Open, Creativity, Destiny)

Taurus, OCD (Open, Creativity, Destiny)

Sacral (Jupiter) Glyph

Sacral (Jupiter) Glyph

Throat (Mercury) Glyph

Throat (Mercury) Glyph

Perspective Glyph

Perspective Glyph

SB

How can everyday language be more accommodating of emotional nuances?

MRL

I think we are already doing that through different forms of language. Emojis, gifs, memes, etc.: these are all a new (but also ancient in terms of pictographs) method to state our very complex emotions. I’m interested in the idea that language is built for speed, and we can say an extraordinary amount in very well-chosen words or symbols, and this means it seldom succeeds in achieving perfect clarity. We learn at a very young age that ♥ means “love,” $ means “money,” and ☠ indicates “danger.’ We naturally interact with street signs and logos, we replace text with emoticons, or we suggest our moods by using glyphs, which have become intuitive tools in our everyday lives. The visceral quality of signs and symbols and our innate disposition to interact with them has always fascinated me and has become an entry point into my work.

SB

What larger concepts are you trying to grapple with in your work?

MRL

Other than my glyph works, my other big body of work is largely titled Bondage Baggage. I really love this work (and I’m still deep in the process of figuring it out) and feel connected to it for various reasons. BB was inspired from actual luggage I would see coming down the conveyor belt in the Kathmandu international airport. These bags were made from all types of materials: boxes, luggage, and unidentifiable shapes wrapped tightly in tarps, fabrics, tape, and rope. It immediately sparked an interest in me, and over the course of six or so years I documented them. I have a large archive of images from then, and from that sprouted the idea to create them with similar materials. These works are about labor, immigration, family, diaspora, self-preservation, privacy, and travel. I then learned that this type of luggage is wrapped similarly in numerous developing countries around the world, which I recognize as a type of language.

SB

What glyph do you think artists and designers need the most in 2020 ? Can you please come up with a new one?

I think we all need the glyph to protect ourselves from STRESS. That is my main downfall. It gets the best of me, but I’m sure it does for most living under the pressure of these times.

—Somnath Bhatt